How rewarding big audience numbers is counterproductive

2022-04-15 11:17

by JAMES BREINER-ijnet

Numbers don’t lie, but people do. And worst of all, people lie to themselves about what numbers mean.

The Big Lie in media metrics for years was the Biggest Number. Media publishers got away with touting their total monthly page views or unique visitors as their “audience”. This was a bit like saying their audience consisted of the people walking past a newsstand and glancing at the front page headlines.

The light went on for me a decade ago when I saw that the vast majority of visits to my clients’ websites lasted 10 seconds or less. Users were clicking but not necessarily reading.

And I found confirmation for my conclusions in a famous 2014 Time magazine article, What you think you know about the web is wrong.

The author, Tony Haile, said research by his internet metrics consultancy found that 55% of some 2 billion web visits lasted 15 seconds or less. People were clicking on his clients’ articles, but not paying attention. The publishers were delivering eyeballs to their advertisers, but those eyeballs might have been glazed over or giving the ads a mere glance.

Haile touted alternative metrics he called the Attention Web, in which the measures that mattered were how much time a user spent on a piece of content, whether they scrolled down through the text and images, and how often they returned to the website.

Supply is infinite, demand is finite

Haile used data to show how the articles that readers spent the most time on were the least frequently shared on social media. In other words, shares and likes were no indication of the value of an article to readers.

He argued that by using metrics of attention, rather than clicks, advertisers would have incentives to produce more creative ads rather than gaudy, intrusive junk. And consumers would benefit because publishers would have incentives to produce quality content, not volumes of sensationalized clickbait.

In the eight years since, Haile has kept at his vision of the Attention Web by designing “a sustainable business model for quality on the web”. He founded Scroll, the ad-free subscription news service designed to share revenue among publishers based on the time readers spend on their sites. Scroll has since been bought by Twitter, which is aiming to offer a subscription service.

Loyalty, the best measure

Over the past few years I’ve written several times about the importance of attention and engagement, rather than total users and page views, as the key metrics in news publishing.

And lately I’ve been collecting articles that go into greater depth on how to measure, analyze, and act on the data related to the Attention Web. They place a premium on how frequently a user comes to a website, the most recent visit, and how much time they spend. The aim of these metrics is to identify which users appear to be getting the most value from the content and might be willing to subscribe, donate, attend an event, or purchase products or services from a publisher.

- The Membership Puzzle Project has prepared an excellent guide to the metrics that matter, and how publishers can act on them, in their Developing Membership Metrics post. It starts with the basics: how to create value for your users and how to convert loyal readers into members, as well as some relevant case studies.

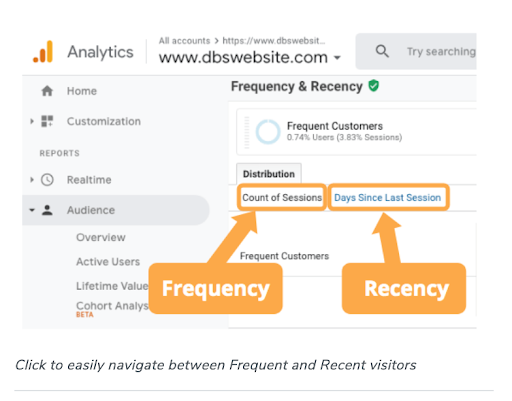

- DBS Interactive offers clear definitions of user recency, frequency, and engagement in Google Analytics Made Easy: Frequency and Recency. This article includes screenshots of Google Analytics pages and how to find the relevant data. It explains how to analyze the information and convert it into an action plan.

An international team of journalists, working with the London School of Economics, and supported by the Google News Initiative, has developed an extensive guide on putting metrics to work with artificial intelligence: How can AI help build audience engagement and loyalty.

- The Google News Initiative’s Reader Revenue Playbook takes you step by step through a process for thinking about, analyzing, and executing a reader revenue program. Much of it is the kind of basic marketing training that journalists don’t typically learn in school or on the job.

- Kristopher Crockett covers the basics in his post Measuring Web Visitor Loyalty if Your Site Offers Pure Content. He also does a good job of explaining how to interpret this data for improving performance.

Rewarding the wrong thing

Many publishers and editors are still getting it wrong. Too often they reward reporters for the number of stories produced daily, the number of social media shares, and other traditional measures of quantity and not quality (See Elizabeth Anne Watkins: Journalists are rightly suspicious of ad tech: they also depend on it).

But audience metrics aren’t even the half of it when it comes to the ways media organizations can misuse and misinterpret numbers. They measure success by revenue growth while they might be losing money on every sale they make. Or they fail to measure how much fuel they have in the tank (cash for operations) until a lender or investor decides to pull the plug.

But we will leave that issue for a future post.

This post originally appeared on James Breiner's blog

Photo by Campaign Creators on Unsplash