How Big Tech dominates EU's AI ethics group

2022-04-11 12:02

To Cecilia Bonefeld-Dahl, director of DigitalEurope and a former IBM executive, the EU's expert group was "a very diverse multi-stakeholder group with members from all types of backgrounds." Others disagreed (Photo: Mike MacKenzie)

By CAMILLE SCHYNS, GRETA ROSÉN FONDAHN, ALINA YANCHUR AND SARAH PILZ-euobserver

In 2016, Oxford professor Luciano Floridi attempted to interest the EU in the ethics of artificial intelligence.

"The number of people who told me that was not an issue, that I was wasting their time, is remarkable," recalled Floridi in late 2020.

-

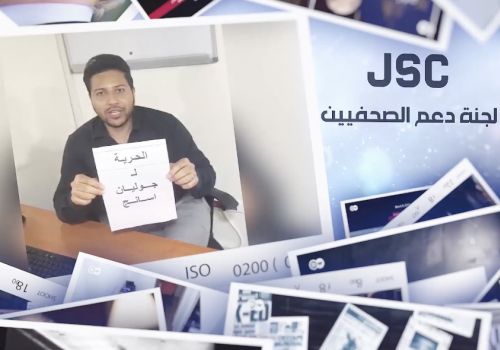

Academics critical of Big Tech are less likely to apply for positions funded by tech companies than tech-positive academics (Photo: Infocux Technologies)

He persevered. Over the next years, as the European Commission set out to regulate AI, the ethics professor would become one of the pivotal experts advising the commission.

But Floridi, like many other experts that advised the EU, had extensive funding ties to Big Tech, raising questions over possible conflicting interests and the outsize influence of business interests on the EU's AI policy.

Expert advice, by industry

In 2018, the European Commission set up a "high-level expert group" (HLEG) that would advise the EU on ethical guidelines and investment policy for artificial intelligence.

Despite the responsibility for drafting the EU's ethics guidelines, few of the expert group members were ethicists. In fact, 26 experts – nearly half of the group's 56 members – represented business interests.

The remainder consisted of 21 academics, three public agencies, and six civil society organisations.

Google and IBM had a seat at the table alongside large European firms like Airbus, BMW, Orange, and Zalando. Through DigitalEurope, a business association where most major tech firms are members, Big Tech had another direct advocate in the group.

To Cecilia Bonefeld-Dahl, the director of DigitalEurope and a former IBM executive, the expert group was "a very diverse multi-stakeholder group with members from all types of backgrounds." The DigitalEurope director proclaimed herself a "strong believer of this diversity."

Others disagreed.

"Only six people representing civil society is very, very low," said Thibault Weber, who represented the European Trade Union Confederation, an umbrella organisation for European trade unions.

"It was not a democratic process at all," Weber continued. "The commission appointed the group [and] we don't even know the criteria". Weber's ETUC struggled to get a seat on the group and was admitted only when a subsidiary trade union withdrew to make room for them.

Internal documents reveal that the EU had initially foreseen more civil society experts and less corporate representatives.

Asked about the make-up of the group, an EU spokesperson highlighted members' "multi-disciplinarity, broad expertise, diverse views, and geographical and gender balance." The official explained the low number of ethicists by stating the group's "intensive work didn't only focus on ethics."

Tech-funded academics

Publicly available information reveals that at least nine of the expert group's academics and civil society representatives were affiliated with institutions that had funding ties to Big Tech, often worth millions of euros. This included academic institutions, like the TU Munich, INRIA, TU Vienna, Fraunhofer Institute, TU Delft, and DFKI.

Luciano Floridi has had long-standing ties to Big Tech: one profile about Floridi, which he retweeted, referred to him as the "Google philosopher".

The Digital Ethics Lab at the University of Oxford, headed by Floridi, is funded by Google and Microsoft. For a paper on AI principles, published during his time on the EU expert group, he declared direct funding from Google and Facebook.

In 2019, while also on the EU expert group, Floridi joined Google's advisory council for the responsible development of artificial intelligence, although Google cancelled the council just a week after its announcement following public outcry.

Another academic on the EU's expert group, Andrea Renda, held the "Google Chair of Digital Innovation" at the College of Europe, which offers prestigious graduate courses on the EU, from 2017 until 2020 – throughout his involvement in the EU expert group.

At the same time, Renda served as a senior research fellow at the Centre for European Policy Studies (CEPS), an influential Brussels think-tank with dozens of corporate members including Google, Facebook, and Microsoft at a price of €15,000 per year.

The three tech giants were part of a CEPS task force on AI, chaired by Renda, which spoke of "the enormous promise" of artificial intelligence, despite "challenges". More recently, Renda led a CEPS study on the impact of the EU's proposed regulation on AI for the commission.

Declaring interests

Experts that were appointed in a personal capacity had to act "independently and in the public interest" and have no conflicts of interest.

Floridi and Renda did not see a conflict of interest between the funding and their role as experts. Floridi commented that "all my research and advisory work is undertaken with full academic freedom and without influence from funders."

Renda explained that "neither of these two activities really interfered with my membership of the HLEG: I was an independent member, and acted as such, contributing very proactively to the HLEG's work."

He had "successfully applied" for the College of Europe position that Google funded, and Google had not participated in the selection process or ever interfered in his activities. "As an academic, I really do not take sides with any private or public power," Renda said.

Other academics say funding does have an impact. Mohamed Abdalla of the University of Toronto said "money does not necessarily change someone's viewpoint," but there is "self-selection."

Academics critical of Big Tech are less likely to apply for positions funded by tech companies than tech-positive academics.

According to Abdalla, who has compared the lobby strategies of Big Tech to those of Big Tobacco, "the issue is overinflation of that view in academia or policymaking."

It is unclear if any experts declared conflicting interests; the commission denied a request for the expert's declarations of independence on the grounds that they contained personal data. Nor is it clear if the commission verified the absence of conflicting interests.

The digital rights advocacy group Access Now, one of the few civil society organisations on the group, receives funding from tech companies too.

Daniel Leufer, Europe Policy Analyst for Access Now, said the organisation had called out the industry dominance in the group and pushed for regulation and red lines.

But it is a fine balance. "We're massively critical when there is a reason for critique, but we're not an anti-tech lobby either," Leufer added. "There's no black and white, and we work with tech companies to ensure that they improve their practices."

Luke Stark, a Canadian academic who refused Google funding, said the fact that in AI research it is nearly impossible to stay away from industry funding is a huge problem. "It really explains a lot of the mess we are in with these systems."

Ties between Big Tech and non-business experts

Hover over individual elements to see their connections or select them directly to learn more. You can also expand the descriptions by clicking on the three dots at the left (on the computer) or at the bottom of the visual (mobile version). We reached out to all expert group members displayed in the visualisation, and have included their comments, if received.

'Red lines' watered-down

Dependence on Big Tech tools caused concerns within the expert group too. In one of their first meetings, the experts group got into a heated discussion.

The topic: could the group use Google docs to collaborate?

"I could not believe it," one expert said. "If there is one group that cannot work on Google docs, it's the AI expert group of the EU." The group decided to work on a different system in the end.

Sources said another debate flared up, when Google's representative, Jacob Uszkoreit, proposed copy-pasting a part from Google's ethics guidelines into the EU recommendations.

"With the guidelines per se there's nothing wrong, but what Google does in practice is not okay, and that is what made people mad," told Sabine Köszegi, professor at the Technical University of Vienna."We said, 'sorry – but no'", Thiébault Weber of ETUC recalled.

Perhaps the most overt display of influence came when the expert group considered developing red lines – applications of AI that the EU would outright prohibit.

Thomas Metzinger, a German ethicist, had been asked to lead the working group on red lines. After several meetings, Pekka Ala-Pietilä, the group's chair and a former Nokia executive, told him to remove any reference to "non-negotiable" uses of AI.

Industry representatives, Metzinger said, gave an ultimatum: "this word will not be in the document, or we are leaving." Red lines disappeared from the agenda.

Instead, the group identified "opportunities and critical concerns raised by AI" and recommended seven "key requirements", like safety, transparency, and non-discrimination, that AI would need to meet.

The group's policy recommendations on regulation "ended up being a rather watered-down part of the overall report", said one expert, Ursula Pachl of the European Consumer Organisation BEUC.

And the "watered-down" recommendations of the expert group were not binding. Only five of the seven principles were used in the AI regulation the Commission proposed in April 2021.

Two were excluded: the EU Commission, in a stealthy footnote, wrote that "environmental and social well-being are aspirational principles" but "too vague for a legal act and too difficult to operationalise."

Auditing AI

As the debate on the AI regulation has shifted to the floor of the European Parliament, many of the experts have moved to new projects.

To Luciano Floridi, the auditing of AI systems appears to be the new frontier.

"We have moved from principles to practices, to requirements, to standards, and guess what happens next: someone takes that as a business," the Oxford Professor said in late 2020.

Floridi said he was interacting with "some major companies" that were looking to "make a lot of money" doing the "auditing of AI as a service once either soft regulations or hard regulations are coming into play. So, watch that space."

Google, Microsoft, Jacob Uszkoreit, and Cecilia Bonefeld-Dahl did not respond to our requests for comment.

Facebook, now rebranded and reorganised under the Meta umbrella company, said: "We support independent research and public debate on how technology, including AI, affect society. When we make financial contributions to advance the public debate, we don't tie our contributions to specific positions or research outcome."