How can artificial intelligence help increase audience engagement with the news?

2022-02-16 07:43

How can artificial intelligence help increase audience engagement with the news?

By: Marcela Kunova-Journalism

Newsrooms can use new tech to solve a few headaches, like making science journalism more accessible or increasing reader loyalty with tailored content recommendations

Successful solutions are never about looking to build a new product but about correctly defining what problem we are trying to solve.

That was the approach of more than 20 news organisations from across the world who worked together last year on addressing some of their problems, using artificial intelligence (AI) technologies. The Collab Challenges - as these experiments are known - are organised by JournalismAI, a project of Polis, the journalism think tank at the London School of Economics and Political Science (LSE) and supported by the Google News Initiatives.

Many outlets were looking at new ways to reach audiences they are not serving properly or to increase the value of their journalism and reader loyalty.

Reaching younger readers

One of the participants was Ketil Moland Olsen, senior project manager at Media City Bergen, who was looking at better ways to reach younger readers who seldom read the news.

Thanks to the data collected from several newsrooms, he and his team realised that the 18-to-30-year-olds often struggle to understand the news because they do not know the background of the stories or even their protagonists, who are typically older. However, they have the same appetite for news as the older generations and want to learn more from journalism.

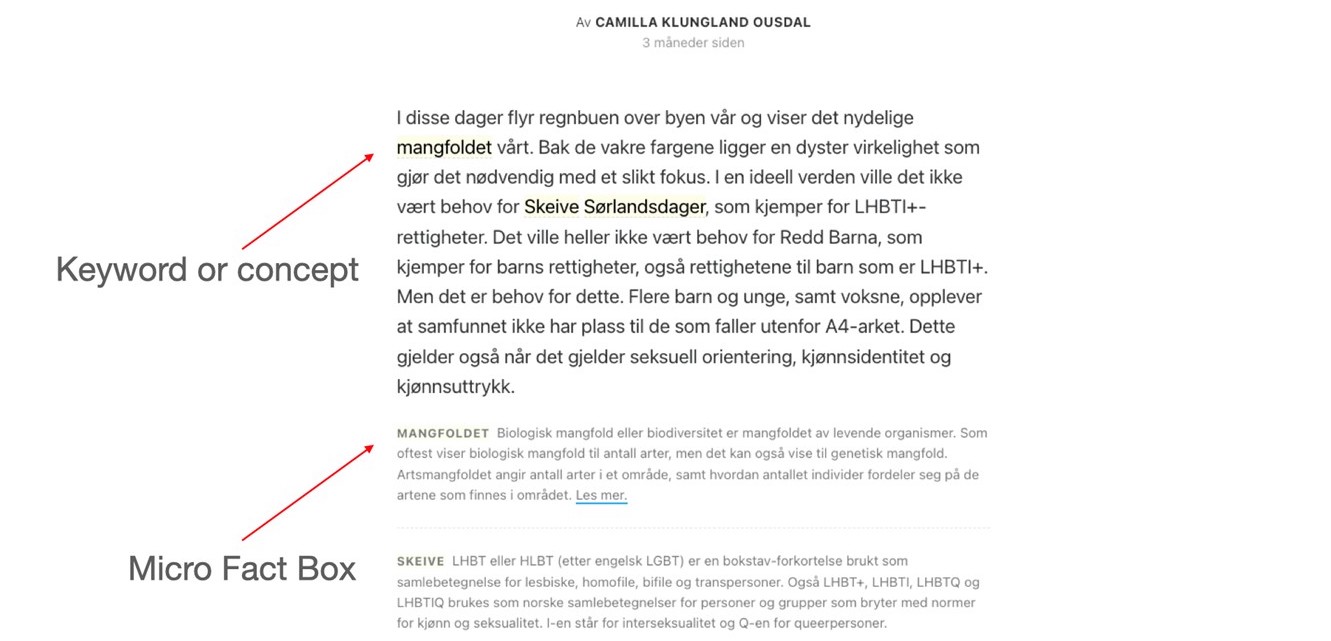

After testing news content with a sample of younger readers, the team started building a tool that would identify difficult topics and uncommon words that journalists often take for granted. They then came up with a “micro fact box” - a small explanatory box that unrolls when the user clicks on these words that the tool highlights in the article. This way, the reader has a choice to learn more about the topic or a person if they want to, or continue to read undisturbed.

Micro Fact Box prototype. Fact boxes between the paragraphs expand into visibility when the user clicks on a highlighted keyword or phrase in the text. Courtesy Media City Bergen

For the moment, the text is pulled from Wikipedia and it is not editable by the newsrooms but the team is looking to change that in the future.

Getting the balance right

There is a fine line between being helpful and being obtrusive or coming across as patronising. So the question is - how much background is too much?

There are several ways the team looks to define how many unfamiliar words need to have a micro fact box. One way is to identify the user as young or a new subscriber and present them with more definitions, assuming they have less knowledge. Conversely, older and longtime subscribers can be given fewer keywords.

But other scenarios are being explored, for example, building an algorithm that learns how often a user looks up the facts and then present them with more or fewer explainers in the future. Another possibility is to offer new subscribers a quiz where they can test their knowledge and then set up a profile for them.

All this comes with ethical questions around tracking users, GDPR and testing people’s knowledge. On the other hand, the tool needs user data to work properly.

This could be solved by giving the user a choice of how many explainers they want, a bit like when you are setting up your gaming profile as easy, medium or difficult.

But the challenge with the user-led approach, said Olsen, is that people tend to overestimate their knowledge of many topics or are not completely honest with the news outlet or themselves.

Understanding climate science

A similar approach was tried by Meik Bittkowski, head of R&D at Science Media Center Germany, and Marco Lehner, technical product developer at public service broadcaster Bayerischer Rundfunk.

They realised that younger and less educated audiences have a harder time understanding climate change stories and journalists get often tired of explaining the basic concepts all over again.

So, when publishing climate stories, the team experimented with a fact box that gives the user fact-checked explanation of climate science, complete with traceable reference to the source, be it a climate expert or a study published in a scientific journal. They hope that this transparency will help increase public trust in science and journalistic sources.

Unlike the micro fact box, these explainers are written by journalists and are editable ad-hoc. This is important when it comes to science, since data may need frequent fact-checking and updating. The ready-made fact boxes can also be used in multiple articles and may come in handy when reporters at different desks need to cover climate change as well as their usual beat, be it breaking news, economy or sport.

Reader loyalty

Another news outlet looking to boost audience engagement was South China Morning Post (SCMP) where deputy digital editor Shea Driscoll wanted to come up with a better way to recommend relevant content to keep readers hooked for longer.

Almost every news site has some version of the "Read more" section populated with content that editors pick using editorial judgement. The catch is that most humans think of a small number of articles that can be linked, rather than exploring the whole website.

But what does better mean when it comes to content recommendation? Is it something that will educate the reader in more depth on the same topic, or an altogether different article that will broaden their horizons?

To crack this question, Driscoll’s team analysed content performance across the SCMP website and mapped what stories people read after they finish the first one. They put together an algorithm that works a bit like a shopping website recommending additional items based on “people who bought this also bought that.” This could be from any other section of the website and not related to the first story at all.

The results were surprisingly encouraging. When testing the tool, the team found that readers who saw content recommended by the algorithm were 75 per cent more likely to come back for more. Even better - those who read one article and were recommended another one from a different section were twice as likely to read an additional piece from a third section of the website, which significantly boosted content consumption.

The way the recommendation was positioned mattered too. When it appeared in the middle of the article and the user needed to actively click on it, they were more likely to read the piece. However, if the article started after the first one finished (infinite scrolling), the user was more likely to drop off.

Driscoll said that this feature could play an important role in SCMP’s subscription strategy since reader loyalty and the amount of content they read are important factors in retaining subscribers.