A Journalist Suggesting Favorite Tools to work wth... Apps to transform an image into a text, data into maps and graphics, flights tracking ....

2021-10-29 09:44

My Favorite Tools with Freelance Journalist Théo Englebert

by Olivier Holmey- GIJN

For the latest installment of GIJN’s My Favorite Tools series, we spoke with French freelance reporter Théo Englebert, who drew acclaim last year for revealing that Rwandan Colonel Aloys Ntiwiragabo, who is suspected of participating in that country’s 1994 genocide, had been living in France for at least 14 years.

Théo Englebert. Image: Courtesy of the reporter

A self-taught investigative reporter, the 30-year-old Englebert did not go to journalism school and has never worked on a newsroom staff. While holding a series of jobs outside journalism through his early 20s, a habit of researching stories in his own time eventually convinced him that he might be able to report professionally.

In 2017 he co-authored his first investigation, for BuzzFeed News, a story that looked into allegations of nepotism within the French far-right political party, National Front. He has since written for online news outlets StreetPress, Vice, Mediapart, and Le Poulpe, as well as for the magazine Les Inrockuptibles and the French daily newspaper Libération.

Recent investigations have looked into the French government’s use of private jets and helicopters to deport migrants, the dreadful living conditions in a prison near Paris, the disconcerting spread of radical Islamism behind bars, a refugee camp where migrants reported feeling like prisoners, and the trial in the Rwandan capital Kigali of Paul Rusesabagina of “Hotel Rwanda” fame.

An avid compiler of data, Englebert advises journalists to avoid software released by large corporations. Instead, he recommends free and open source products, which are transparent about the way they work and the snags they encounter, thereby giving investigative reporters peace of mind regarding the safety of the technologies they employ.

Here are some of his favorite tools:

Linux

“Linux is an open source operating system. I would never consider doing investigative work on proprietary, closed operating systems,” Englebert says. “Given the values that journalism is supposed to further, I do not understand the use of software whose code is not published and to which ordinary people cannot freely contribute.”

“I use Linux as you might use any operating system. The main difference is that I manage my machine myself, I know what’s on it, I know what I want, what I don’t want, what I use it for, I make all of these decisions myself,” he adds.

Because the defects of open source software are revealed publicly and corrected very frequently, Englebert says these systems are more secure than private, closed operating systems, where users have to trust the patches released by, say, Microsoft or Apple. “You can’t be sure of the security of such software, since you can’t audit their codes.”

Xapian

“Xapian is an indexing platform and search engine. It can be told to index either all of the files on a computer or some of them only, be they emails, PDFs, or text files,” Englebert explains. “It is a very practical tool when you have, as is my case, huge court files, administrative reports, appendices to reports, and accounting data. The only stage that takes a bit of time is indexing the documents, but once that’s done the search function runs very fast.”

Englebert uses Xapian as his desktop search engine, since it allows him to search for a word, a phrase, or a sentence. “I can set specific search criteria that allow me to find what interests me within huge amounts of documents. It’s much more efficient than the default search engines in a desktop environment,” he says.

As part of his research for his Mediapart investigation into Rwandan exile Ntiwiragabo, Englebert had to sift through dozens of gigabytes of documents. “I wasn’t aware that they contained a memorandum from … France’s domestic intelligence agency, which proved to be very useful to my investigation,” he says. “It’s because I use this tool systematically that I sometimes come across nuggets buried deep within huge files that I otherwise might not have seen, for example this memo.”

Tesseract

“My investigative work on Rwanda has me dealing with a lot of images of documents made in the 1990s,” Englebert notes. And Tesseract, which is an optical character recognition tool, nicely complements Xapian, he says, since it helps convert older documents into searchable text. “For optical character recognition to work, documents have to be somewhat legible: Tesseract can’t work miracles, and the user always has to manually correct the transcription when the documents are old,” he explains. “That being said, the tool does save me a lot of time.”

After receiving hundreds of documents from the French government, which he input into a database, Englebert used Tesseract to search for names on Rwandan government publications, enabling him to document a sophisticated network of associations set up in France by alleged Rwandan genocide suspects on the run. That investigation was published by Mediapart.

“I decided to run character recognition on a series of old documents, including a genocide suspect list that had been drawn up by the Rwandan government in 1996, then I added those names to new sheets of this database,” he explains. “I used a mathematical formula to check for names that appeared both in the network that I had documented in France and in this list of suspects. There were indeed a number of matches, some of which became the focus of the article.”

Map-Making Tools

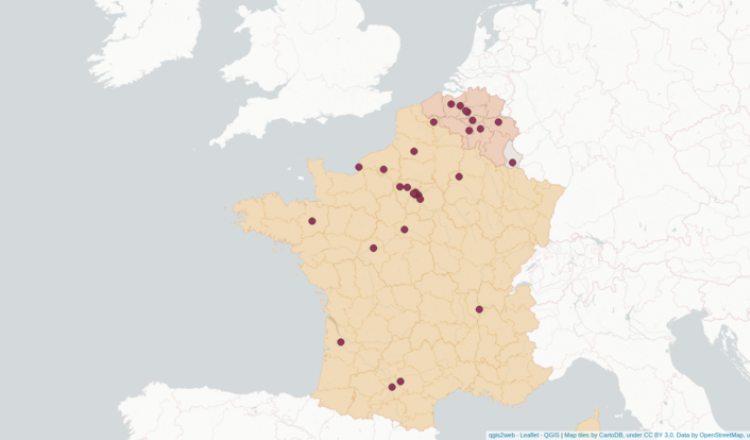

Englebert used QGIS, a map-making tool, to generate an interactive geographic map from his database of exiled Rwandan genocide suspects. “It’s a basic map featuring dots,” he explains of the result. “When I go over each dot, the map refers me to the corresponding information in my database. If I ever were to publish it alongside an article, it would make the investigation more entertaining to readers, but beyond that it also helps me make sense of my research as it is sometimes more intuitive than long columns of data.”

Englebert used QGIS to create an interactive map connecting suspected Rwandan genocide exiles. Image: Screenshot

“Likewise, I use Gephi to generate network maps, which make the relationships listed in my table more tangible,” Englebert adds. “Gephi maps are also interactive: when I hover on a dot, it highlights all the people and associations and companies that an individual is connected with, which is very practical. The visualization validates the inferences I have already made about the connections between certain people and certain places.”

Flight Tracking Tools

“I systematically use planespotting databases when reporting on the deportation of migrants,” Englebert says. “These tools allow us to trace the flight path of deportees, thereby substantiating articles on the subject.”

His BuzzFeed investigation revealing how private aircrafts were being used for French deportations was based on information from the ADS-B Exchange database, which publishes air traffic data. But because that database can be expensive, he also recommends free databases like Flightradar24.

“There are also online databases, including Airfleets, which allows you to find out the types and registration numbers of planes operated by any given airline, as well as whether they are still in operation,” he says.

“I learned from official bulletins which airline had won the French Interior Ministry’s tender to deport refugees. By looking up this airline on Airfleets, I found a list of its airplanes. As I knew which type of aircraft the tender was for, I could easily determine which of those planes might end up serving this purpose,” he explains. “Having their registration numbers handy saves me time when I am covering a deportation.”

Google Earth

The town of Bweyeye, in southern Rwanda, which the reporter visited to report for Libération on Paul Rusesabagina of “Hotel Rwanda” fame. Image: Courtesy of Théo Englebert.

When Englebert was reporting in southern Rwanda for Libération, he found satellite imagery, especially Google Earth, useful both for scouting and for follow-up research once back from assignment.

“This region of Rwanda is essentially a war zone so you need to act accordingly while you’re there — you don’t necessarily approach every building that interests you,” he explains. “It’s helpful to look up online, through satellite imagery, those things that you were only able to observe from a distance, in order to study them from a different perspective.”

Englebert also uses Google Earth to scout his reporting locations before going into the field to report. “Initially, it gives me a sense of where I’m going and of the local landmarks. Central Africa and the continent’s Great Lakes region are places where topographic maps are not made available to the public,” he notes, because of the active military situation. “Satellite imagery is therefore all the more useful in these areas,” he adds, although he says it only “partially mitigates the lack of information.”

Google Earth can also be used to check facts and “go back in time,” to see what was at a certain location at a certain point in the past. “I used it that way too, to check military positions,” he says. “For example, if a source shows you what they say is a new military position, you can verify from satellite imagery that it actually appeared at that time rather than 20 years ago.”

More generally, Englebert recommends that investigative journalists encrypt both their equipment and their online conversations, to protect the anonymity of their sources but also as a matter of course. “When you mail a letter you first place it in a sealed envelope, and when you leave home you lock the door behind you,” he notes. “Journalists should be similarly cautious.”

Ultimately, he sees himself as a reporter, not just an investigator. “I’m neither a cop nor a prosecutor,” he concludes, pointing out that all journalists should check their facts and protect their research. “I simply tell factual stories.”